Your Home Is Your Castle- Even If It’s a Not a Castle

Blog by Laura Villani and Arun S. Maini

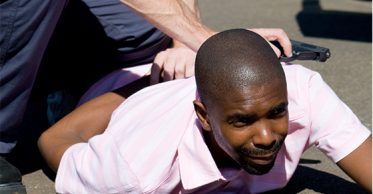

Five young men are chilling in a backyard- four are black and one is Asian. No drugs, no booze, no loud noise. Police wander into the yard and start asking questions. One cop steps over a short, waist-high fence and barks at one of the men to “keep your hands where I can see them”. The police start demanding to see everyone’s ID. One cop asks the young Asian man- Mr Le-“what’s in the backpack?” The young man panics, with good reason, because he’s got drugs and cash and a gun inside. He gets chased down and arrested.

So was that a legal arrest?

The trial judge said it’s problematic but look, it’s pretty serious because there’s a gun and there’s drugs. And it was a rough ‘hood, no doubt not the kind where the judge hosts his dinner parties. So the judge wagged a finger at the cops but let the evidence in.

The Court of Appeal didn’t see any problem with the trial judge’s reasoning and upheld the conviction.

The Supreme Court of Canada said “Not so fast”. The Supreme Court, in a strong, principled decision that rang out like a clarion call, made it clear that the police conduct was illegal, unacceptable, and a violation of the most cherished freedoms that we possess- our rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Can the police enter my backyard without a warrant?

Nope. That’s called trespassing. The police need a warrant or some emergency basis to intrude onto the privacy that you enjoy in your backyard.

What if it’s in a rough neighbourhood?

Doesn’t matter. That’s what the government tried to say to justify this police shakedown. Maybe you’re not fortunate enough to reside in Forest Hill, or even the manicured suburbs that cops like to barbecue in. Doesn’t matter: you have just as much right to peace and quiet and to be free from police sticking their nose in as the judge does when he goes home, or the cops who arrested Mr. Le- or anyone else.

Being poor doesn’t entitle you to less freedom.

What if it’s not my backyard?

That’s a bit trickier. You can keep the cops out of your own backyard, but can you keep them out of your neighbour’s? In legal terms, did Mr. Le have a “reasonable expectation of privacy” in his friend’s yard?

In this case, the Supreme Court said that they did not have to answer that question, because the police so clearly violated Mr. Le’s rights, by arbitrarily detaining him, that the location where those violations occurred did not have to be examined.

So why did the police do it?

The police justified their intrusion into the backyard on the basis that the neighbourhood where they were patrolling was a high-crime area- a townhouse complex with subsidized housing. In other words, not the kind of neighbourhood the police would choose to live in.

This kind of random police check, called “carding” is intended to be a way that the police can troll through a neighbourhood and randomly detect and deter crime. But part of the problem with that approach, besides the fact that it is not based on any actual legal grounds, is that the people the police target most are visible minorities.

That’s a fact.

The police also tried to justify it after the fact by saying “See? We were right. He had drugs and a gun.” But of course the police don’t report on all of the times they chase down a person of colour, search him, and come up empty-handed.

What is an arbitrary detention?

A “detention” is when the police are standing there talking to you or investigating you, and you are not free to walk away. Even if the police do not tell you to stay put, chances are that when an armed police officer is questioning you, you do not feel like you have the right to simply walk away from him. Too many black people, to give one disproportionately targeted group its due, are legitimately afraid to test what might happen if you walk (or run) away from police. That is called a “psychological detention” and is a realistic fair way to look at the situation.

A detention is “arbitrary” when the police have no grounds to detain you. In other words, they didn’t see you sell drugs; you do not fit the description of a suspect in a crime that just happened; they didn’t pull you over for speeding. They just don’t like the look of you. Or maybe it’s purely random. But this kind of “fishing expedition” by police is illegal.

What does race have to do with it?

A lot, actually. The experience of racial minorities when it comes to being stopped and questioned by police is quite different from that of a white middle-class person. Not only are minorities targeted more often by police, but when they are stopped, they tend to be more fearful and less likely to walk away. So members of racial minorities tend to experience “psychological detention” more readily, and for that reason it is so important to recognize a police shakedown for what it is. In this case, all five young men were minorities, and they were in what the police call a “high-crime” area- so they were highly susceptible to being targeted by police.

So what happened to Mr. Le?

The Supreme Court said that the police had no right to trespass into the backyard, no right to question the young men or ask for their ID, and certainly no right to ask Mr. Le what was in his backpack, chase him down and search him.

The arbitrary violation of Mr. Le’s rights in this situation was so serious that the Court decided that even though he was carrying a gun, the evidence had to be excluded because to do otherwise would be to undermine the fundamental rights of all of us to walk down the street, chat with friends, or enjoy a backyard BBQ- without being hunted down by police.

Laura K. Villani is a second year student at Osgoode Hall Law School.

Arun S. Maini is a criminal lawyer and former prosecutor with over 20 years of experience.